If you want to learn how to cook, start with eggs. That's my advice. Eggs are, after all a powerful symbol of something new happening - new life, a new beginning. But there is another reason. Somehow eggs have become an equally negative symbol. When someone says, 'Oh, I can't even boil an egg,' what they are actually saying is, 'I can't cook anything at all.'

That's why anyone wanting to make a start should begin by understanding eggs. Yes - even how to boil them. By cracking egg cookery (sorry about the pun) and simply knowing how to boil, poach, scramble, make an omelette and so, you're going to give your cooking confidence a kick-start and ensure you will never go hungry. You'll also be able to offer your friends and loved ones a very quick but pleasurable meal. But that's not all: eggs are a supremely important ingredient in the kitchen, serving the cook in any number of ways. They can thicken soups and sauces, set liquids and baked dishes, they can provide a glorious airy foam to lighten textures and will also, quite miraculously, emulsify oils and butter into a rich smoothness.

What we have to do first and foremost, though, before we even begin cooking, is to try and understand what eggs are and how they work.

A hen's egg, quite simply, a work of art, a masterpiece of design and construction with, it has to be said, brilliant packaging! It is extremely nutritious, filled with life-giving protein, vitamins and minerals. It has a delicate yet tough outer shell which, while providing protection of the growing life inside, is at the same time porous, meaning the air can penetrate and allow the growing chick to breath. It's the amount of air inside the egg that the cook needs to be concerned with. If you look at the photograph to the left, you'll see the construction of the egg includes a space for the air to collect at the wide end, and it's the amount of air in this space that determines the age and quality of the egg and how best to cook it. In newly laid eggs, the air pocket is hardly there, but as the days or weeks pass, more air gets in and the air pocket grows; at the same time, the moisture content of the egg begins to evaporate. All this affects the composition of the egg, so if you want to cook it perfectly it is vital to determine how old the egg is.

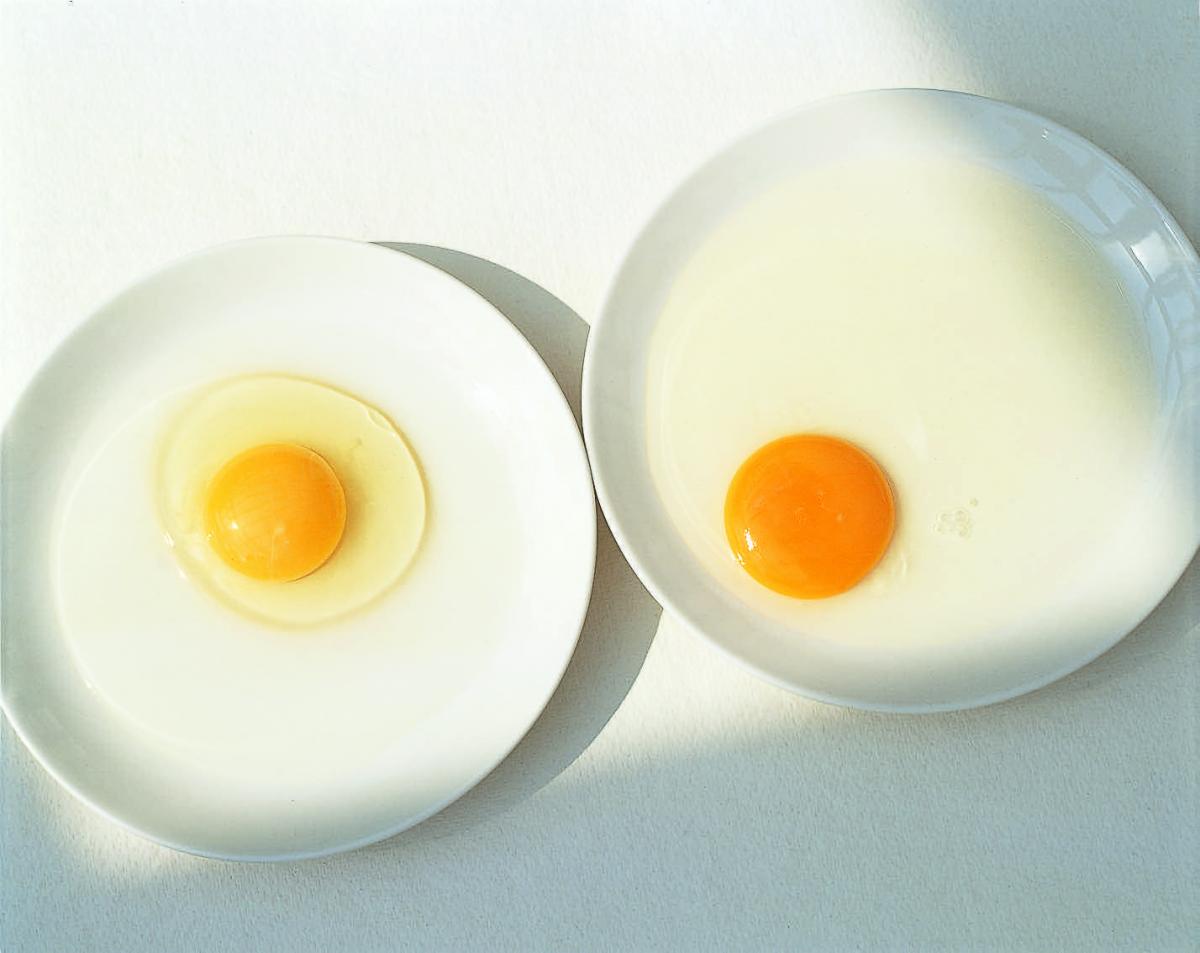

Now look at the photograph on the right and see what the egg looks like when it is broken out. What you start off with, on the left, is an egg at its freshest, with a rounded, plump yolk that sits up proudly. The white has a thicker, gelatinous layer that clings all around the yolk, and a thinner outer layer. After a week, on the right, the yolk is flatter and the two separate textures of white are not quite so visible.

Now all is revealed! You can see very clearly why you may have had problems in the past and why an egg needs to be fresh if you want to fry or poach it, because what you will get is a lovely, neat, rounded shape. Alas, a stale egg will spread itself more thinly and what you will end up with if you are frying it is a very thin pancake with a yellow centre. If you put it into water to poach it, it would probably disintegrate, with the yolk and white parting company. Separating eggs is yet another hazard if the eggs are too old, because initially the yolk is held inside a fairly tough, transparent membrane, but this weakens with age and so breaks more easily.

So far, so good. But we haven't quite cracked it yet because, just to confuse matters, a very fresh eggs isn't always best. Why? Because we have another factor to take into consideration. If we get back to the presence of air, what you will see from the photograph on the left is that inside the shell is an inner membrane, a sort of safety net that would have protected the chick if the egg had been fertilised. When the egg is fresh, this is like a taut, stretched skin; then, as more air penetrates the egg, this skin slackens. This explains why, if you hard-boil a really fresh egg, peeling off both the shell and the skin is absolute torture. But if the egg is a few days' or even a week old, the skin will become looser and the egg will peel like a dream.

So far, so good. But we haven't quite cracked it yet because, just to confuse matters, a very fresh eggs isn't always best. Why? Because we have another factor to take into consideration. If we get back to the presence of air, what you will see from the photograph on the left is that inside the shell is an inner membrane, a sort of safety net that would have protected the chick if the egg had been fertilised. When the egg is fresh, this is like a taut, stretched skin; then, as more air penetrates the egg, this skin slackens. This explains why, if you hard-boil a really fresh egg, peeling off both the shell and the skin is absolute torture. But if the egg is a few days' or even a week old, the skin will become looser and the egg will peel like a dream.

What all this means is, yes, you can cook perfect eggs ever time, as long as you know how old they are.

How to tell how old a raw egg is while it is safely tucked away in its shell could seem a bit tricky, but not so. Remember the air pocket? There is a simple test that tells you exactly how much air there is. All you do is place the egg in a tumbler of cold water; if it sinks to a completely horizontal position, it is very fresh; if it tilts up slightly or to a semi-horizontal position, it could be up to a week old; if it floats into a vertical position, then it is stale.

The only reason this test would not work is if the egg had a hairline crack, which would allow more air in. That said, 99 per cent of the time the cook can do this simple test and know precisely how the egg will behave. To sum up, the simple guidelines are as follows:

Number one on the list here (unless you happen to know the hens) is to buy your eggs from a supplier who has a large turnover. Boxes now (and sometimes the eggs themselves) carry a 'best before' date. What you should know is that this date, provided the egg box is stamped with the lion mark, corresponds precisely to 21 days after laying (not packing), so you are, therefore, able to work out just how fresh your eggs are.

Although it is now being recommended that eggs should be stored in the refrigerator, I never do. The reason for this is that for most cooking purposes, eggs are better used at room temperature. If I kept them in the fridge I would have the hassle of removing them half an hour or so before using them. A cool room or larder is just as good, but if, however, you think your kitchen or store cupboard is too warm and want to store them in the fridge, you'll need to try and remember to let your eggs come to room temperature before you use them. My answer to the storage problem is to buy eggs in small quantities so I never have to keep them too long anyway.

The very best way to store eggs is to keep them in their own closed, lidded boxes. Because the shells are porous, eggs can absorb the flavours and aromas of other strong foods, so close the boxes and keep them fairly isolated, particularly if you're storing them in the fridge.

There is, however, one glorious exception to this rule. My dear friend and great chef Simon Hopkinson once came to stay in our home. He brought some new-laid eggs in a lidded box, which also contained a fresh black truffle. He arrived on Maundy Thursday, and on Easter Sunday made some soft scrambled eggs which by now had absorbed all the fragrance and flavour of the truffle. Served with thin shavings of the truffle sprinkled over, I have to say they were the very best Easter eggs I have ever tasted!

Eggs, I am very happy to report, are out of the firing line on the cholesterol front. It is now believed that the real culprits on this are saturated fat and partially hydrated fat, which eggs, thankfully, are low in. There is more good news, too: even if you are on a low-fat diet, eating up to seven eggs a week is okay. Hooray!

Poor old eggs; just as they recover from one slur, along comes another. Eggs, as we know, can harbour a bacterium called salmonella. Cases of food poisoning, or even death, from eating eggs are isolated but do occur. Therefore, the only way we can be absolutely certain of not being affected is by only eating eggs that are well cooked, with hard yolks and no trace of softness or runny yolk at all. Ugh!

What we all need to do is consider this very seriously and be individually responsible for make our own decisions. Life, in the end, is full of risks. The only way I can be absolutely sure I won't be involved in a car accident (and statistically this is far greater risk than eating eggs) is to never ride in a car. But I am personally willing to take that risk - as I am when I eat a soft boiled egg. So it's a personal decision. As a general practice, though, it is not advisable to serve these to vulnerable groups, such as very young children, pregnant women, the elderly or anyone weakened by serious illness.

Follow us Like us on Facebook Follow us on twitter Follow us on instagram Follow us on pinterest Follow us on youtube

© 2001-2024 All Rights Reserved Delia Online